There are student performances, and then there are student performances. At the Glenn Gould School, the students are mostly in their twenties and are on a career track. One expects both the singers and the orchestra to be at near professional level, and musically, the performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute did not disappoint. It was a thoroughly enjoyable evening.

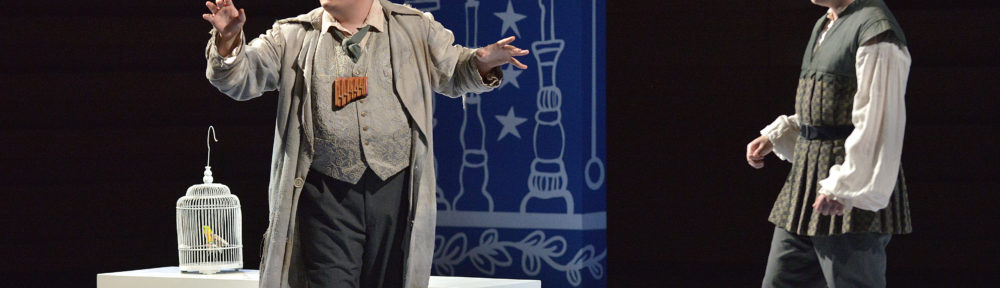

One of the main impacts of these professional training program performances is to introduce the young artists to watch, and the most accomplished singer of the night was baritone Noah Grove (Papageno). His is a light voice, with a seductive vibrato and masterful phrasing. Warm, mellow and intuitively musical, Grove’s sound cocoons the ear. His singing appears effortless. He is also a delightful actor who eats up the stage, and his ability to play with words turns lyrics into conversation. Time, one hopes, will add heft to the lightness.

From the very first note, bass Gabriel Sanchez Ortega (Sarastro) caught the listener off guard. His sound is huge, and my first reaction was that he could not possibly be a student. In fact, he is a GGS alumnus. Mozart wrote Sarastro’s role with notes in his toes. Even career basses have difficulty getting down that low, but Ortega pulled off a few minor miracles. Strong, robust, commanding, his voice galvanizes attention throughout his entire register. At this point in time, Ortega just sings, meaning, his expressive qualities are limited, but once he gets his acting chops into high gear, what a package he will have to offer. The first reaction to his booming, rolling sound is astonishment.

Tenor Zachary Rioux (Tamino) is all over the map. At present, high is equated with loud, and his modulation is very uneven. But, and this is a very important but, there is something about his voice that is absolutely compelling. With a hint of an Italian sob, and an old-fashioned sensibility coating his sound, Rioux is like those tenors of old who did loud and soft, and nothing else. While he sometimes seems to be reaching for the high notes, he does have strength at the top and ease in the middle, but he has to connect to the words more. Forceful would be a good way of describing his voice. There is definitely passion there, and while his sound will never be beautiful, it is on track to be exciting.

Nofar Yacobi (Queen of the Night) pulled off her two notoriously difficult arias with just a couple of glitches. She is a coloratura soprano who is definitely not a chirper. She has bite to her sound, which will make for interesting developments down the road. Her coloratura is precise and clean. Because there is an edge to her voice, Yacobi does not produce pretty trills, but the potential for something goosebump-making is there, which is far more valuable.

The jury is still out on soprano Kateryna Khartova (Pamina). On the plus side, her phrasing is lovely. She understands the connection between words and music, and makes sense of lyrics. In fact, she was one of the best in doing so in the performance. She can also capture mood, and is blessed with a strong top. The downside is that her voice lacks definition. Lyric sopranos are the most common garden-variety female singers, and they need a special quality to rise above their fellows. Khartova has all the elements, but is missing the total package that rivets the ear. Her output needs a spine to tie everything together. I just couldn’t get a handle on her voice.

Marta Woolner as 1st Lady attracted attention. Although the Ladies (Woolner, Mélissa Danis and Georgia Burashko) sang very prettily together, Woolner’s voice reached out beyond the trio. She has a big sound in the making – Verdi, even Wagner? You could hear lushness and luxuriance. For me, Woolner had the most potential of any singer on stage. As for the other Ladies, they certainly had attractive voices, and I hope to hear them again in individual roles.

Even-voiced tenor Christopher Miller gave a good account of himself as Monostatos, although he could have used a bit more power of expression, the three bratty Spirits (sopranos Diana Agasian, Victoria Del Mastro Vicente and Anna Wojcik) sounded suitably childlike, and while soprano Katelyn Bird (Papagena) had trouble being heard above the orchestra, she had lots of energy. Tenor Michael Dodge and baritone Benjamin Loyst did multiple duties as priests, armed guards and slaves, along with tenor Stefan Vidovic as a fellow slave. The cast as a whole served as the chorus and did a fine job as an ensemble.

The 42-member Royal Conservatory Orchestra was certainly impressive under Maestro Nathan Brock. In fact, Brock seems to like speed, and the orchestra literally romped through the overture faster than a speeding bullet. The maestro did slow down where necessary, particularly for moments of wonder or melancholy on the part of Tamino or Pamina, but for me, the most glorious aspect of the music was the majestic way Brock captured the ceremonial choruses. They were blood-stirring moments.

Joel Ivany first made his name as artistic director of Against the Grain Theatre, a company devoted to the creative presentation of opera, which is why this Magic Flute was a disappointment. Admittedly, director Ivany had obstacles. Koerner Hall has no wings, and the soloists had to be his chorus. Anna Treusch had designed an arresting series of freestanding blue and white Masonic banners that people could hide behind, and there were a couple of white benches for sitting, but basically, Ivany never solved the problem of when people were soloists and when they were chorus. There was a mishmash of singers populating the stage at anytime. Ivany also did some peculiar innovations. When Papagano is singing about wanting a girl of his own, he is surrounded by the Queen, the Ladies and Pamina as seductive sirens. Ivany also had the Queen appear silently from time to time as Sarastro’s nemesis, but this was not clearly defined. Ivany is also listed at lighting designer, and in his attempt to mask the chorus, the stage was too dark. In short, the opera was either being over-directed or under-directed, when what was needed for a difficult stage was plain and simple. Ivany should be commended for neatly collapsing the roles of Speaker, Priests, Armoured Men and Slaves into just three singers.

Ming Wong did what she could with costumes on a small budget, but there was no tie-in between the outfits, with each one being its own scattered entity. Treusch’s props ranged from lame (the serpent), to peculiar (bird’s eggs representing the Papageno children). John Gzowski did a great job with the ear-splitting thunder and lightning in the sound design.

The Glenn Gould School Opera, Mozart’s The Magic Flute, conducted by Nathan Brock, directed by Joel Ivany, Koerner Hall, Mar. 20 and 22, 2019.