INTRODUCTION

First let me say that both operas are, for the most part, very well sung and divinely conducted. As well, the COC continues to find interesting new voices to bring to us which is a good thing.

That being said, I have some problems with the staging of The Cunning Little Vixen, and huge problems with the staging of Don Giovanni.

THE CUNNING LITTLE VIXEN BY LEOS JANACEK (1924)

We haven’t seen Vixen in Toronto since 1998 so it is making a welcome return. It is not, however, an opera for all markets. Where some people lose interest is with the plot, where animals and humans interact in a realistic setting. It’s not a fairy tale, nor is it a fable. Rather, it is a story about relationships, and feelings, and the life cycle of both nature and humans, and how we fit together. Janacek was 70 when he composed the opera and his thoughts were on a more philosophical bent, although the source material was a humorous comic strip.

The music is quite lovely in a modernist way (think Debussy and Impressionism), but it is also imbued with folk rhythms that bring a lilt to the score. This is an opera where the orchestra is almost more important than the singing, in as much as it is filled with long orchestral passages, and Johannes Debus and his players give us a lushness that pays tribute to the magic of the forest and the wonders of nature.

Basically, the opera follows the adventures of the vixen Sharp-Ears (soprano Jane Archibald), beginning with her being kidnapped and raised in captivity by the Forester (baritone Christopher Purves) and then breaking free, killing the Rooster (tenor Adam Luther) in the process, her then meeting with the male fox Gold-Stripe (mezzo-soprano Ema Nikolovska) which results in her becoming a mother, and finally her death at the hands of the poacher Harasta (bass-baritone Alex Halliday).

The Forester also plays a central role and is given the final scene where he reflects on his own life in relation to the death of the Vixen. The Parson (bass-baritone Giles Tomkins) and the Schoolmaster (tenor Wesley Harrison), the Forester’s drinking buddies, are also considered major characters, with the Forester’s wife (mezzo-soprano Megan Latham), his dog Lapak (mezzo-soprano Alex Hetherington), and the hen Chocholka (soprano Charlotte Siegel), rounding out the secondary players. In all, there are a whopping 23 singing roles and four different choruses, not to mention seven non-singing ballet roles. Thus, there is plenty for the COC Ensemble (current and former) to do in this opera, along with a host of children from the Canadian Children’s Opera Company. The COC chorus is also very busy and are their usual excellent selves.

Soprano Archibald has the clear bright voice so necessary for the part of the Vixen, particularly in showing the creature’s many moods. Macedonian-Canadian mezzo-soprano Nikolovska as Gold-Stripe displays a fulsome commanding tone, yet one that is imbued with warmth and colour. The rest of the Canadian cast produces the even singing throughout that this opera demands. It really is an ensemble piece. The one import, so to speak, is impressive. English baritone Purves as the Forester brings the right amount of exasperation and reflection, delivered with a hearty, rich sound.

This production comes from the English National Opera helmed by director Jamie Manton and his vision has attempted to capture the very spirit of Janacek’s music with mixed results. His designer, Tom Scutt, has brought to life the forest creatures in imaginative costumes, sometimes very real, other times comic. For example, the Rooster looks like he’s wearing a crown, while his chorus of hens is hilariously clothed in tulle skirts like a corps de ballet. Costume-wise, the production is a visual delight.

Scutt is also responsible for the set, and this is where Manton’s vision falters. The stage is littered with logs. They form the chairs and the buildings and seem very large and heavy as opposed to the delicate creatures that live within them. It’s like a lumber camp. There are also large compartments on wheels with a flat wooden surface on one side, and a seating compartment on the other. They look like the kind of boxes that furniture movers use, and they give a clumsy aspect to the set. Nonetheless, designer Lucy Carter’s lighting bathes the stage in wondrous colours which mitigates the impact of all those logs.

And then there is the big red modern exit sign, almost in the middle of the back wall, that presumably lives on the Four Seasons stage on a permanent basis. I couldn’t help but be fixated by that sign, that clearly doesn’t belong in the opera. It needed to be covered over in some way. It certainly spoils the look of the set.

So, final thoughts. Singing and costumes, yes. Set, problematic.

DON GIOVANNI BY W.A. MOZART (1787)

Help! Please save me from Eurotrash directors. Four opera companies are stuck with this production (Royal Opera, Liceu, Israeli and Houston), but with luck, we may never have to see this artistic crime again.

Mercifully, the singing, for the most part is wonderful and Maestro Debus gives us a reading that is sublime. While Danish director Kasper Holten ignored the text, at least Debus and his orchestra are sensitive to the words and the emotions. I ran into an acquaintance after the performance who is an opera guru – he literally travels the world following opera – who told me that once he saw the idiocy that was happening on stage, he kept his eyes closed and just listened to the glorious singing and the brilliant orchestra.

So let’s talk about what is good in this Don Giovanni – namely the singers, and how wonderful it is to see Canadians (three of them) take pride of place among an international lineup.

The Don himself is performed by Canadian bass-baritone Gordon Bintner. He certainly looks the part – tall and handsome – and he can act up a storm. His voice is smooth and seductive, but I’d like a little more oomph, forza, brio, in other words, a bit more climactic definition to push his singing over the edge. That would just be perfect – the icing on the cake.

The other two Canadians are a matched pair – mezzo-soprano Simone McIntosh (Zerlina) and bass-baritone Joel Allison (Masetto).

I am thrilled to hear a Zerlina who is not a soprano chirper, and having McIntosh’s rich, vibrant mezzo voice is a genuine surprise and delight. Rather than a brain-dead Zerlina, we get a young woman of fire and substance. Let’s hope she comes back to the COC in another significant role. In an opera filled with bass-baritones, Allison presents a lighter, younger tone. He has a pleasant, even voice, but in the best sense, because it is also very expressive. His acting is also terrific.

Armenian soprano Mané Goloyan (Donna Anna) is a little mite of a woman in stature, but when she opens her mouth, a huge sound of shimmering beauty pours out with not a shred of shrillness at the top. Her phrasing is delicious because she can manipulate her voice, pulling back and floating notes, then ringing out in loud declamation. She is a keeper.

Italian bass-baritone Paolo Bordogna (Leporello) absolutely understands the buffa style. In listening to him roll out his words, I could just picture him in a myriad of roles from Figaro to Don Pasquale. He has perfect pacing, perfect delivery and perfect tonal play. His Leporello does not put a foot wrong in his expressive display of both voice and character.

There are two talented Americans in the cast, tenor Ben Bliss (Don Ottavio) and bass David Leigh (Commendatore).

Bliss is another of those light-voice tenors in the Mozart/Rossini repertoire, and they, for some reason, are always taller than their spinto Verdi/Puccini fellows. Thus Bliss presents a handsome stage figure. He is gifted with a gorgeous voice that negotiates both high and low notes with ease. In fact, it is wonderful to hear his seemingly effortless singing. Leigh’s voice is just what you want a bass to be – commanding, fulsome, hearty, authoritative and, when in full force, overpowering.

I’ve saved Romanian soprano Anita Hartig (Donna Elvira) to the end because I found her voice to be singularly unattractive, although she is a formidable actor. I would like to say my response is a matter of taste. Hartig is not a poor singer; she is just not to my liking. Others may thrill to her voice, but I have never taken to a thin, reedy sound with much vibrato. Again, it is a matter of taste, although I appreciate her performance.

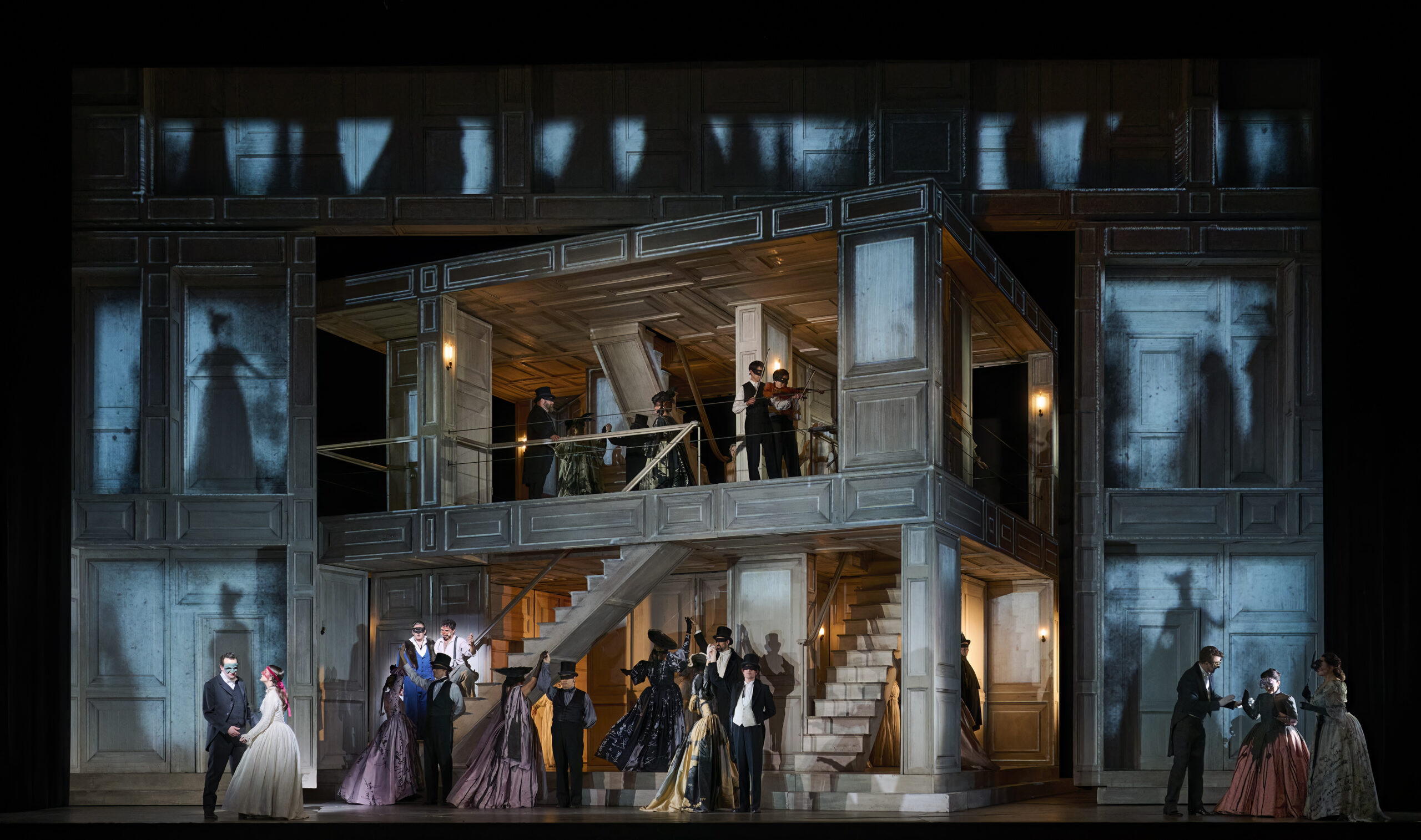

So now we come to English designer Es Devlin’s set. I carefully read director Holten’s program notes rationalizing this revolving snakes and ladders of staircases and doors – a maze that is a prison of illusions, a living hell etc. etc., and perhaps it could have worked if it were better directed and not a ceaseless, meaningless parade. Instead, what we get is people marching up and down and all around for no apparent reason.

Text is also totally ignored. For example, in the Don G/Zerlina seduction duet “Là ci darem la mano”, Holten has the singers miles apart, coming together for one embrace and then parting again. Now that there are surtitles, a director can’t ignore the text. It’s just plain dumb. He could have found other physicality to underline his thesis that the Don is a heartless taker, or a user, or a vampire. As for the Commendatore, Holten has him wandering around like a ghost, which isn’t a bad idea, but since the Don does not react to these appearances, they become meaningless. In other words, the staging makes no sense.

And then there is Danish designer Anja Vang Kragh’s costumes that cross centuries. I don’t usually have a problem with different periods together, but in this case, the look just confuses an already confused world. Leporello comes right out of a Rossellini or De Sica film as some street smart shady character, while Donna Elvira belongs in the 18th century. As for English designer Luke Halls’ projections, they are a mess of symbols and squiggles, and you just give up trying to figure them out after a time. The projections also seem like technology run wild. I do, however, like the part where all the names of the Don’s conquests are written all over the scrim. If only every other visual element had the same force of meaning.

Holten’s ending is infuriating. Don Giovanni is dragged down to hell by singer Bintner miming being in the throes of forces beyond his control, while there are ghostly figures around him standing completely still. It is practically laughable – like an exercise from a high school drama class. (“Okay, Gordie. Mime being dragged down to hell.”) And, oh yes, the epilogue is cut. That’s right, no self-righteous septet from the remaining characters. Holten has created a dramatic ending, but it’s not Mozart as we know it today. Now admittedly, the final ensemble was excluded until the 20th century made it common practice. Apparently, it was presented at the first Prague performance and then never again, so Holten is in his right to drop it. What he doesn’t realize is the shock value backlash. The surprise of the no-show final ensemble overshadows the drama of the Don’s demise.

On the subject of music, however, I have to applaud the fact that this Don Giovanni includes both Don Ottavio’s wonderful tenor arias (“Il mio tesoro” and “Dalla sua pace”), as well as restoring the beefed up Masetto/Zerlina scene. This production seems to be mostly the Prague rather than the Vienna edition.

To be fair, I know people who responded positively to Holten’s vision. I’m just not one of them.