Introduction to Janak Khendry and his new dance piece Life Eternal

Life Eternal is at the Fleck Dance Theatre Nov. 9-11.

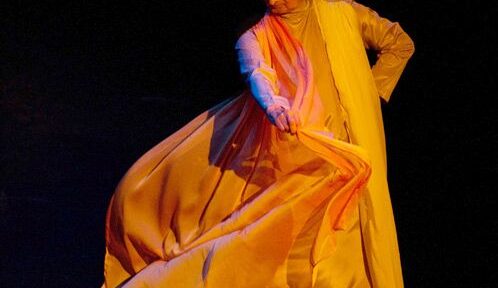

At 78, choreographer/designer/sculptor Janak Khendry is the doyen of Indian classical dance in Canada. Roughly every two years, he produces a gigantic dance piece of sumptuous beauty and deep philosophical inquiry. This year’s offering is Life Eternal, which examines the pathway to immortality in three great religions – Buddhism, Jainism, and Hinduism. When it comes to themes, Khendry is always willing to take on the big picture, so to speak. His repertoire is filled with epic works of lofty purpose. He also designs the gorgeous array of costumes.

Khendry was born in Amritsar in the Punjab, North India, and was a dancing whirlwind from the age of five. His forward thinking parents allowed him to study dance as long as he maintained a high level in his academic studies. Over time he became proficient in four distinct styles of Indian classical dance: bharatanatyam, kathak, sattriya and manipuri. He maintains that his years spent with bharatanatyam guru Swami Muttukumar Pillai in a tiny village in South India were the happiest of his life. After graduating with a B.A. in English and Art History, he took a second B.A. in metal sculpture.

Khendry moved to the United States in 1961, where he attended Ohio State University for his Masters in sculpture. He also studied modern dance, including Graham, Limon and Cunningham techniques. He then relocated to New York City where he spent 16 years, both as a performer of Indian classical dance, and as the gallery director of the New York Sculpture Centre.

Khendry moved to the United States in 1961, where he attended Ohio State University for his Masters in sculpture. He also studied modern dance, including Graham, Limon and Cunningham techniques. He then relocated to New York City where he spent 16 years, both as a performer of Indian classical dance, and as the gallery director of the New York Sculpture Centre.

Canada became his new home when he met Toronto dentist Herschel Freeman who became his life partner. Khendry moved to Toronto in 1979 and opened the first gallery in Canada specializing in glass sculpture. The gallery was a fixture in Yorkville for 22 years. He also founded his dance company which has been going strong for almost four decades.

The Interview (wherein Janak Khendry talks about Life Eternal).

I have to say, Janak, that you don’t shy away from vast topics when you make your dances.

Simple themes are not for me. I’m a sucker for punishment, but I also want to create a work of art on the stage.

Where did the idea for Life Eternal come from?

It was during a conversation with friends when we were discussing different paths to immortality. The idea just jumped out and I grabbed it. I envisioned a work showing three different religions, each with its own language and traditions, and all of them striving for the universal truth of immortality, but in different ways. It was very tough creating the piece because I had to come up with three parallel stories. I did not want to preach religion. Rather, I wanted to explore the philosophy behind achieving immortality. Originally, I wanted to call the piece Immortality, but my advisors felt the word had too much religious connotation.

I know you consult with what you call your research advisors as part of your mammoth preparation for a new work.

Dr. Tulsiram Sharma and Dr. Narendra Wagle are both specialists in South Asian Studies. Their input and guidance is invaluable. I’ve known them for years.

Why did you not include Islam in Life Eternal, the other great religion of the Indian subcontinent?

I’m very careful. Religion in general is a touchy subject, but with Islam, especially so. I felt I would need permission from Moslem leaders to broach the subject, so it seemed easier not to go there.

What is your next step in the creation process after research?

I write a complete step-by-step draft of the story line, which I send to my music director, Ashit Desai, in Mumbai. Ashit and I have worked together for over 20 years. I also send the lyrics I want, which for Life Eternal, are verses from the sacred texts, the Vedas and the Gita. When the music is composed, Ashit then sends back a CD. This is done three or four months before rehearsals start. I listen to his compositions over and over again until my body absorbs the music. Slowly, movement starts to come in my head, and I make drawings of the choreography under the musical notes on the score. I document everything.

I see that to explain something so abstract as striving for immortality, or freedom that transcends time and space, as you call it, you use concrete narratives to illustrate the concept.

Yes. The Buddhist section has four characters: the Buddha, his young son, who is about 14, and two converts. One is a poor, downtrodden female street sweeper, while the other is a cruel man, a murderer, a thief, yet, as followers, both come to sit at the feet of the Buddha. The have all found love, peace and happiness.

And the Jain story?

The main character is King Payesi who is a horrible person until he hears the sermon of a Keysi, a holy man, that touches him deeply. Everything changes for him and he gives up his earthly treasures. In disgust, his wife Suryakanta poisons him, but he is reborn as a very pious human.

And the narrative that illustrates the Hindu path to immortality?

Markhendye is a sage who has reached a high level of spirituality. The god Indra sends all kinds of things to tempt the sage to betray his spiritual self, but Markhendye does not react. The gods are pleased that a human being is so pious, and he is given the blessings of the supreme god Shiva and his consort Parvati.

These are three very distinct sections. Do you bring them together at the end?

Three dancers, one representing each story, are seen walking to the back of the stage together. They symbolize freedom.

Three dancers, one representing each story, are seen walking to the back of the stage together. They symbolize freedom.

How did three different stories, representing three different religions, impact the choreography?

The movement came about according to what the subject matter dictated. Some of it is in definite styles of dance, other parts are my own movement creation. There is no end to what the human body can do to be expressive.

There are 14 dancers, seven men and seven women. Are they all local, or did you have to import some from India?

All of them are from Toronto, but have different backgrounds. Most are of Indian descent, but there are dancers from Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, for example. The dancer playing King Payesi is a Moslem. I treat my dancers with love and respect because they give life to my work, which makes them a very important part of my life.

Eternal Life, choreography by Janak Khendry, is at the Fleck Dance Theatre, Nov. 9-11.