(Happily, DanceWorks brought Fragments to Toronto on Mar. 3, 2012, so I could enjoy Emard’s brilliant work once again. In the intervening two years since the premiere in Ottawa, he has added titles to each fragment, and I’ve added them into the original review.)

Montreal’s Sylvain Emard has managed to stay true to himself while creating a universal appeal for his dances. Unlike some of his Québecois colleagues, he has not prostituted his talent to the European presenters. Rather, he made them notice his choreography for the fine craftsmanship that it is. The hallmark of an Emard piece is that his dancers dance.

As a choreographer, Emard never disappoints, and his latest piece Fragments-Volume 1 is a masterpiece. This CDF world premiere is made up of four short dances that reach into the very soul of vulnerability. Manuel Roque portrays a man who is literally beside himself with restless angst. Catherine Viau is a young women trying to reconcile her inner and outer personas. Laurence Ramsay and Roque portray a push-me, pull-me couple. While these dance stories are absolutely compelling, it is the third vignette that is Emard’s crowning glory. Veteran Montreal actress Monique Miller’s portrait of profound loneliness is simply one of the most beautiful dances every created.

Richard Lacroix’s clever set design evokes both a prison and a cave, most suitable for Emard’s claustrophobic world. Above the black box performing area is a low grill of lights that give off beams resembling steel bars. They bathe the dancers below in uneven squares. Designer André Rioux has worked these lights to pin spot precision, focusing on a face, or a back. At times, front projections create waves of light on the back wall, and thus a dancer’s body is fragmented into these separate patterns. Rioux is not afraid to use bilious yellow or green for dramatic effect. There is also a mobile made of strings of shiny fragments above the light grill. When the light falls on them, it is not to portray a magic world of brightness, but one symbolic of the shattered lives below. The evocative music by Michel F. Côté and Jan Jelinek runs the gamut from whining industrial electronica to chords of melancholy blues.

Roque’s vignette (Dans mon jardin…) begins with him upended on a chair. We see him first in a flash of light mirrored in an explosive sound of cacophony. Whether straddling the chair, head to the floor, feet in the air, or standing erect, or crouching in pain, he is never still. He shudders. He convulses. His body seems to be enduring a never-ending barrage of electrical shocks. He is a perpetual motion machine that can find no rest or respite. It is inner agony writ large.

Roque initiates what will be a recurring motif in all the short dances, and that is, the detailed gestural language Emard has created for touching the head. In many different ways, the head becomes the epicentre of the body, and all four dancers are given movements which isolate the head as the psychological and emotional heart of the dance.

In Viau’s piece (Emoi, émoi), Emard plays with the concept of front and back. She faces us, and she turns away. She moves forward, and she moves back. Whereas Roque’s trajectory is chaotic, Viau is regimented in straight lines, perhaps a metaphor for her uptight personality. Her face is bland when looking at the audience, but as soon as a hint of emotion appears, she turns away, and we see the silent scream of her heaving shoulders. If Roque is wild in his body, Viau is measured, although there are hints of physical explosions that never materialize.

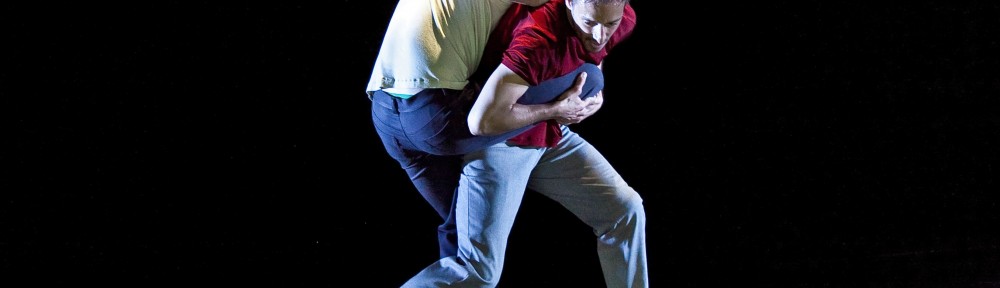

The male duet (Bicéphale) is made up of both synchronized and individual movement. The cleverness here is that even when Roque and Ramsay are dancing the same steps, there is tension rather than easy camaraderie. The dance employs lots of limb thrusts to the point where the bodies seem to be in conversation with each other, rendering these outcrops of arms and legs as a sign language of their own. Ramsay seems to be the more even-tempered one, and Roque the more mercurial. The times that their arms are around each other’s shoulders are a fraud because Emard shows us their true love me/hate me feelings when they are engaged in their solo interior monologues.

Miller (Absence) begins on a chair. Just sitting, she seems to be consumed in grief. Emard has given her small detailed movements that speak in large volumes. One hand gingerly rests on the wrist of the other, then turns that hand gently around. She touches her heart, her face, her knee. When she does stand up, she seems distracted, not sure of where to go. Nothing jars in this solo. She is all halting grace, but oh, the sorrow that emanates from her very being. The most poignant moment is Miller’s soulful, detailed movements that accompany the voice-over that recites an on-line dating profile where both she and her ideal man are described. She is clearly a woman of culture and worth. Is she the pearl in the oyster that has yet to be found? Or, is she the gemstone that was discarded as glass.

That all four performers are wonderful is a given. Emard only works with acting dancers/dancing actors. Roque, Viau and Ramsay have a suppleness of grace that goes well with Emard’s fluid choreography. He is such an organic dancesmith that each movement pattern seems to grow logically out of the one before. His work is of the whole cloth and that is why he is a great choreographer.

Fragments-Volume 1 is part of a diptych, and I must say that I am now on pins and needles to know where Emard plans to take the next part. Whether another collection of exquisite miniatures, or something different, his choreography will always radiate humanity at every turn, conveying his innate compassion as a creator and an artist.

CANADA DANCE FESTIVAL, Sylvain Emard Danse – Fragments-Volume 1, Choreography by Sylvain Emard, Performed by Monique Miller, Manuel Roque, Laurence Ramsay and Catherine Viau, NAC Studio, Ottawa, Jun. 05, 2010