Photo by Jeremy Mimnagh

The full title of this impressive play is There is Violence and There is Righteous Violence and There is Death or, The Born-Again Crow.

The Born-Again Crow (for brevity’s sake) is a sprawling behemoth of a play.

This magnum opus won Métis playwright Caleigh Crow the 2024 Governor General’s Literary Award for Drama, and I suspect the judges were impressed by the work’s immense imagination. Within the framework of reality that slips in and out of magic realism, Crow presents a troubling picture of a lost young woman.

At one point in the play, Beth (Tara Sky) proclaims that she is a half breed with mental issues, and that describes her situation exactly. The playwright however does not leave her to flounder but allows Beth to become empowered by the play’s end. That is a given. The audience knows that beforehand. The playwright’s concentration is not on the fact that Beth finds agency, but how she arrived there. Clearly for Crow, Beth has found the mechanism to triumph over colonialism and capitalism, both curses faced by Indigenous people. But Crow also plants a lingering doubt about Beth in the ambiguous ending.

Beth’s journey begins with the character at her lowest ebb. She has just been fired from her job at the Superstore, and poverty has forced her to come back home.

She is also facing possible police charges because her firing triggered a massive flame out and she trashed the store. This was no ordinary trashing, however. Beth’s rampage included assaulting a coworker, setting a fire, and in a final act of defiance, pinning a raw steak to the manager’s office door. (Later in the play we find out that the flashpoint that sparked Beth’s meltdown was the manager’s refusal to raise her salary by one dollar, an insignificant amount but one that would have eased Beth’s hand to mouth existence).

What she finds at home is problematic.

First, she must confront the toxic relationship with her mother, the fragile, nervous, reclusive Francine (Cheri Maracle) who is on disability and in therapy. And then there is the annoying, persistent, dangerous Tanner (Dan Mousseau), the white boy next door who has tried to dominate her life, and with whom Beth shares a disquieting past, with forced sex implied.

In an attempt at reconciliation, Francine has transformed the backyard into a place of refuge for Beth, and Shannon Lea-Doyle’s remarkably realistic set is the lily that gilds the text. There is a table and chairs with loungers scattered about, plus a white picket fence, the backdoor to the house and the wall hemming in the garden.

There are also a series of strangely shaped, abstract art bird feeders, and I’m sure that Doyle designed these off-kilter structures to mirror the fraught tension and emotional turmoil that anchor the bedrock of the play. Francine herself enjoys feeding the birds and thinks that this hobby might be a good distraction for Beth in her time of troubles. In doing so, Francine has set in motion a future that she could never have imagined.

Photo by Jeremy Mimnagh

Coinciding with the sullen Beth’s tension-filled first encounter with her overwrought mother, we see a shadowy figure just beyond the fence. This turns out to be Crow (Madison Walsh) who at first brings Beth little gifts like an earring or a shard of glass, becoming over time a sort of special friend.

Crow however is much more than that. Beth discovers that Crow can talk, but she is not the good fairy of storyland. Crow is a subversive character who feeds Beth seditious and antisocial advice, but she is also the éminence grise who enables Beth to find empowerment through resistance and rebellion. Crow conjures up the image of the Trickster who is an integral part of Indigenous mythology. For the playwright, Beth is discovering her indigenous roots through Crow.

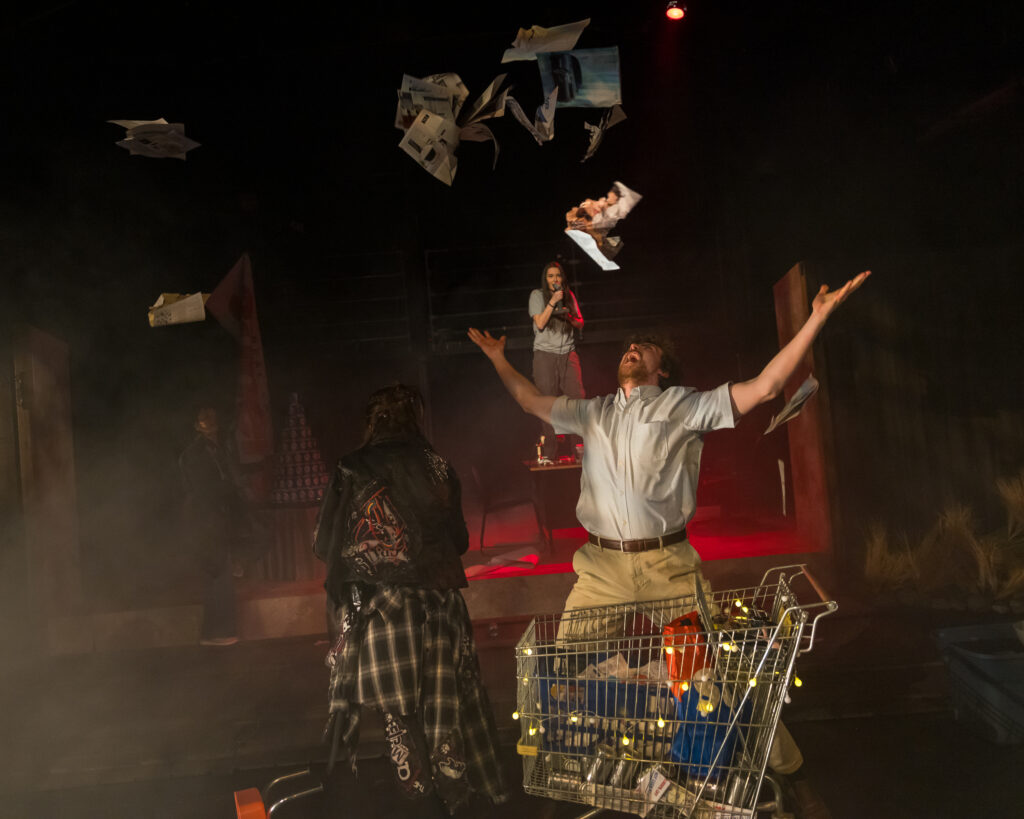

In short, under Crow’s influence, Beth becomes a fighter, a warrior, and when she finally unleashes her battle cry, it is magic realism on steroids. Kudos to director Jessica Carmichael and her design team for crafting a stunning visual coup de théâtre that made the audience literally gasp.

Objectively speaking, The Born-Again Crow is a play built on metaphors.

Beth’s lashing out against the manager of Superstore who provoked her violent rage in the first place is an indictment against the brutality of capitalism. In fact, the very name Superstore is its own metaphor. When legions of crows begin to gather in the backyard and leave their droppings on the houses and cars of the neighbours making their life unbearable, it is Indigenous revenge against White Man’s colonial repression as epitomized by Tanner’s White Man’s superiority. As for the narcissistic gossip writer Jane (played by Mousseau), she stands for all the indifferent people who fail to grasp the reality of the plight of others.

Francine’s frailty and down-trodden spirit are the result of colliding with the White Man’s world. The fact that Francine’s house is on a cul-de-sac represents the boxing in of Indigenous spirit. Beth’s fractured mental health and her abject poverty mirror the plagues that affect the Indigenous community in large measure. The talking crow is a validation of the mystical beliefs of Indigenous cultures and heralds their reawakening. The fact that the other actors become crows as needed informs the strengths or weaknesses of their own characters. Beth becoming obsessed with feeding the birds represents her growing communication with nature which harkens back to her Indigenous roots and reverence for the land. As the play progresses, the tide turns, and Beth and Francine grow stronger than their white neighbours. Is this reversal of fortune symbolic wishful thinking or real truth?

One could go on and on detailing the metaphoric threads that permeate the very structure of the play, but in short, The Born-Again Crow’s mission as a play is to carry playwright Crow’s message to Indigenous people.

The title can be taken two ways – that the born-again crow is a catch-all phrase that embraces violence, righteous violence and death, or the born-again crow is an opposite concept, that the “or” of the title denotes an alternative pathway for Indigenous people. I find the second idea more interesting.

The usual bromide is that Indigenous people must find the strength to rise against the barriers that have kept them down and in a final instance, if necessary, exercise righteous violence. I think that playwright Crow is absolutely against this notion. Being reactive and always playing catch up is weakness. Righteous violence comes from a position of weakness, and the acceptance of weakness is a living death. That’s what the long title of the play means in my interpretation.

A more genuine course of action is to become a born-again crow whose strength and warrior spirit is proactive, aggressive and in your face. Born-again crows have experienced a spiritual rebirth. They’re not coming from behind but are leading the charge. In fact, they’ll never come from behind again. They define themselves and don’t let others determine who they are.

Photo by Jeremy Mimnagh

Carrying this ringing message is a cast of actors, a director, and a team of craft people, but there are flaws in the production that should be addressed.

In terms of acting, I had some problems with the women, although collectively they give a strong ensemble performance.

Sky can certainly embrace character, but she has a very idiomatic speech pattern. She literally pronounces every last letter of every word giving her a very pronounced and punctuated delivery which I found distracting. Maracle seems to play Francine on one anxious note, while Walsh needs to be stronger in her slippery slyness. She needs more presence.

On the other hand, the uber talented Mousseau presents sterling character studies in the four roles that he plays. (Tanner, Jane, Jim, head of the neighbourhood committee, and Stephen, the Superstore manager). He is literally a chameleon who can make himself unrecognizable both in physicality and voice. Each character is a stunning transformation, and I’m sure that some audience members looking at the program after the show were shocked to find out there is only one male actor listed. I first spotted Mousseau in a play at Hart House several years ago and spoke to his future greatness then. This superb actor has never disappointed me.

Director Carmichael has a talent for moving characters naturally around the stage and that includes the crows. She has cleverly made them more human than birds. Similarly costume designer Asa Benally has fashioned a crow wardrobe that evokes the birds without looking silly. Hailey Verbonac’s lighting evocatively plays with light and shadow, the former glaring in the magic realism scenes and the latter reflecting the muted tones of real life. Chris Ross-Ewart has provided the driving score that mirrors Beth’s journey.

As a play, The Born-Again Crow is dense, provocative, and in certain respects, very disturbing, particularly the ending which hints at Beth’s weakness. It is also daring in its mix of reality and magic realism that avoids confusion through skillful writing. Playwright Crow also leaves us asking questions. From whom did Francine inherit the house in an expensive enclave? Why does Francine refer to Beth’s boss by his first name in a familiar fashion? Who is Beth’s father? Why are the ancillary characters so stereotypical?

Nonetheless, there is no denying the fact that the play packs a wallop. It presents a tortured picture of life set beside a picture of hope. Francine and Tanner might not be able to change, but will the born-again Beth make a successful life for herself? Playwright Crow leaves us with that tantalizing final question.