This is the age of the auteur opera director. With the endlessly  repeating standard repertoire a fact of opera life, companies are now searching for productions that give a fresh take on the classics. New opera, of course, is always going to be fresh.

repeating standard repertoire a fact of opera life, companies are now searching for productions that give a fresh take on the classics. New opera, of course, is always going to be fresh.

Thus, directors and their visions are what drive opera productions these days. The COC’s winter season provides a textbook case of what works and what doesn’t.

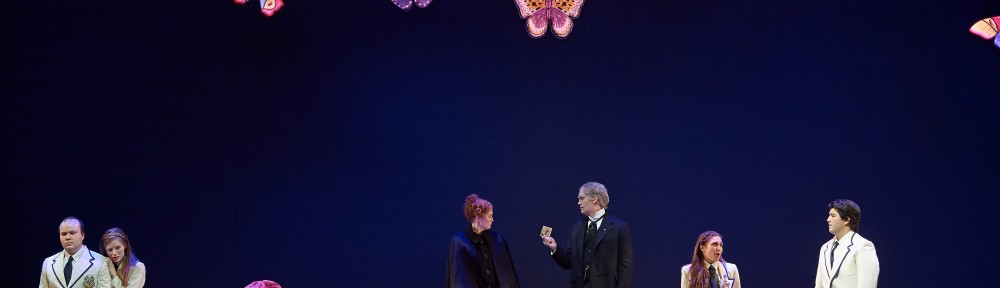

Canadian director Atom Egoyan has done a superb job in finding a fascinating entree into Mozart’s Così fan tutte. Since the heart of the opera is an experiment – Can women be faithful to their lovers? – why not set the opera in an actual modern day science lab with Don Alfonso as the teacher. The chorus is on stage for most of the opera as the Don’s eager beaver students, following the main action carrying their clipboards for note-taking. Debra Hanson’s school uniforms are delightful. In keeping with the educational motif, fencing outfits are substituted for soldiers’ uniforms.

The metaphor that anchors Egoyan’s vision is the butterfly which clearly represents freedom. The science lab, however, is festooned with giant pins to pierce the butterflies and render them into specimens. Hanson’s fabulous set includes gorgeous hanging butterflies to keep the concept in front of our eyes. The question before us is: just how much freedom is allotted to lovers, or should they be pinned by their obligations?

Egoyan also makes prominent use of the famous painting by Frida Kahlo – Two Fridas – that shows both the heartbreak and the warm glow of love. Egoyan and Hanson have also added whimsy. When the fiancés are sailing away, students provide a slow parade of ships balanced on their heads – a sop to 18th century fashion. There is also a podium whenever a character has a great pronouncement to make.

The chorus of students also helps out in the direction of the solo singers. They hold them down, they hold them up, they help them dress, they manage props – all in an effort to make the experiment work – all, as it were, in the cause of science. The entire opera is filled with delicious visual details that support the science experiment.

In the final analysis, this is a production that works, because everything hangs together. Opera companies around the world should be lining up to showcase this very clever and beautifully conceived Così fan tutte.

Every time I attend a Johannes Debus performance, my admiration grows. The conductor  finds nuances in every crook and cranny of the score. His tempi are always perfect, even though his slow times present challenges of breath control to the singers. His judicious pauses are downright risky, but also exciting. In short, he gives the listener complete satisfaction. As for his players, the obbligato work was superb. The use of the pianoforte for the recitatives added to the richness of the sound.

finds nuances in every crook and cranny of the score. His tempi are always perfect, even though his slow times present challenges of breath control to the singers. His judicious pauses are downright risky, but also exciting. In short, he gives the listener complete satisfaction. As for his players, the obbligato work was superb. The use of the pianoforte for the recitatives added to the richness of the sound.

The performance i attended featured the COC Ensemble singers which provided an embarrassment of riches, giving us eight lovers instead of four.

The first act Fiordiligi, soprano Aviva Fortunata, has a big, soaring voice of infinite spinto coloratura possibilities. Is there a Lucia, or even a Brunhilde in her far future? She absolutely nailed her big aria Come Scoglio. In contrast, the second act’s Sasha Djihanian is much more of a true lyric soprano who can pull her nuanced voice back into sotto voce with ease. Her coloratura is not the most facile, but the musky quality of her voice emits an exotic sound.

Mezzo-soprano Charlotte Burrage, the Act 1 Dorabella, is blessed with a seductive lyric voice of great clarity of tone, overlying hearty expression. Act 2’s Danielle MacMillan has a bright sound and beautiful legato phrasing with spinto qualities that speak to heavier roles in the future. It is a surprisingly big voice at this early stage of a career.

The Ferrandos were two quite different tenors. Act 1’s Andrew Haji has an expressive voice as smooth as silk, replete with Italianate sob. It is a beautiful light sound blessed with an even legato flow. Act 2’s Owen McCausland displayed some breathiness in his high notes, but he took great risks in pulling his voice back. It is a strong lyric sound that commands the ear and speaks of a deeper and darker future.

The Guglielmo of baritone Cameron McPhail (Act 1) sported a romantic sound that kept  growing stronger throughout the act. It is, at the moment, a light lyric baritone, pleasing in tone. Baritone Clarence Frazer (Act 2) is definitely on his way to the Verdi/Puccini repertoire. He has a powerful, robust voice with a gruffness of expression so identified with that fach. He does, however, have to make sure that what is gruff does not turn woofy and obscure pitch.

growing stronger throughout the act. It is, at the moment, a light lyric baritone, pleasing in tone. Baritone Clarence Frazer (Act 2) is definitely on his way to the Verdi/Puccini repertoire. He has a powerful, robust voice with a gruffness of expression so identified with that fach. He does, however, have to make sure that what is gruff does not turn woofy and obscure pitch.

The Don Alfonso (bass-baritone Gordon Bintner) and Despina (soprano Claire de Sévigné) were a constant in both acts. Bintner is, of course, too young for the role, but he has a complete mastery and ease of stagecraft. His, like many low voices early in their career, is a sound in progress. It is even, pleasant, and expressive, but in want of the well-developed heartiness to come. His career should be stellar. Sévigné is a coloratura soprano with bite. Her voice may have the quick mercury of her fach, but nonetheless, it produces a sound that is much more than feather light, and therefore, more interesting.

Which takes us to A Masked Ball. Mercifully the music elementsare strong because the production is the quintessence of Eurotrash. In the case of opera, Eurotrash  encapsulates theatrical visions that add nothing to the music because they are lost in the creators’ own distorted assessment of their own intellectual acumen. Eurotrash holds the audience captive as the creators subjugate the hapless patrons with a confused parade of metaphor and symbolism. The good thing about Eurotash is that sooner or later it will end. (It’s not just Europe that produces artistic crimes. In Canada, I call these infuriating productions Canajunk.)

encapsulates theatrical visions that add nothing to the music because they are lost in the creators’ own distorted assessment of their own intellectual acumen. Eurotrash holds the audience captive as the creators subjugate the hapless patrons with a confused parade of metaphor and symbolism. The good thing about Eurotash is that sooner or later it will end. (It’s not just Europe that produces artistic crimes. In Canada, I call these infuriating productions Canajunk.)

This particular production was created for Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin by the talentless team of co-directors Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito. Their collaborators who executed their vision are set designer Barbara Ehnes and costume designer Anja Rabes. All parities should be put in chains and made to attend Così fan tutte (see above).

There are two versions of A Masked Ball, one that depicts the assassination of the Swedish King Gustav 111 at a masked ball in 1792, and one set in pre-revolution Boston in 1690 where governor Riccardo replaces the king. The shift to the New World was to placate the censors who deemed the king’s murder was too close in time to 1857 when Verdi wrote the opera. Wieler and Morabito have elected to do the Boston version, updating America to around 1960.

The single set is the ballroom of the Arvedson Palace Hotel. (The directors are being cutesy here because Arvedson is the name of the fortuneteller in the Swedish version.) The glaring pink and white tables and chairs look like an ice cream parlour. There are also theatre seats that don’t face the ballroom stage, a bar in the far corner, and a balcony walkway above. What this hotel ballroom has to do with the story is anybody’s guess. In their program notes, the co-directors justify their vision with key words like civil rights, youth culture, the fragility of identity and so on. None of these ideas, however, translate to the stage.

Here is just a short litany of the horrors that Wieler and Morabito have inflicted upon us, all of which denudes the power of Verdi’s magnificent music.

Riccardo and the men of the chorus disguise themselves for the trip to the fortuneteller by rolling up their pant legs, taking off their jackets, and loosening their ties. They just look plain dumb. The fortuneteller Ulrica is inexplicably blind. While the orchestra plays the menacing music that accompanies Amelia gathering the special herb beneath the gallows that will make her stop loving Riccardo, the lights of the chandeliers are blazing. Where’s the scary midnight darkness? As for the two hanging bodies in a ballroom…And let us not forget that vegetation, aka gallows hill, is depicted as trees and branches under glass as the ballroom pillars light up from the inside.

Renato, the close friend who kills Riccardo, conducts his important scenes in his pajamas  and bathrobe. In fact, at one point, the entire male chorus is in pajamas. The page Oscar has been turned into a brat who shows up at the masked ball in the dead swan dress Icelandic singer Björk wore to the Academy Awards in 2001. Incidentally, there are hardly any masks at the masked ball. All in all, the costumes are a disaster, particularly Amelia’s various pantsuits which make her look dowdy and years older than she is supposed to be.

and bathrobe. In fact, at one point, the entire male chorus is in pajamas. The page Oscar has been turned into a brat who shows up at the masked ball in the dead swan dress Icelandic singer Björk wore to the Academy Awards in 2001. Incidentally, there are hardly any masks at the masked ball. All in all, the costumes are a disaster, particularly Amelia’s various pantsuits which make her look dowdy and years older than she is supposed to be.

Wieler and Morabito do have a couple of good ideas. They have given Riccardo a silent Jackie Kennedy clone first lady, and Amelia’s and Renato’s son is manifested by a real little boy. These silent characters are quite effective, weaving in and out of the action, particularly when Renato hands over his son to the conspirators, Tom and Samuel, as surety for his commitment to the murder plot.

The cast, thankfully, is very strong. Canadian soprano Adrianne Pieczonka’s voice might be a little harsh on the high end, but she packs a vocal wallop of passion. Her delivery is downright exciting. American tenor Dimitri Pittas as Riccardo has an ease of high notes. He is very believable as the dandy governor with a carefree manner. More importantly, he does negotiate that big sing that is at the heart of Verdi. Renato is performed by talented British baritone Roland Wood. He can certainly play with his expression, and pump up the volume of his commanding voice when needed.

Ulrica requires a big, throaty sound and Russian mezzo-soprano Elena Manistina was born to play the all important hearty mezzo characters so beloved of Verdi. Her big juicy voice is thrilling. Oscar was originally a trouser role for a coloratura soprano. Canadian singer  Simone Osborne is totally suited to the role with her sweet sound and feathery delivery. Italian bass Giovanni Battista Parodi as Tom, and American bass Evan Boyer as Samuel prove to be very effective conspirators. Both are good, clear-throated singers who understand that restraint is a stronger position than melodramatic villainy. Canadian baritone Gregory Dahl shows off his robust sound in the small role of Silvano.

Simone Osborne is totally suited to the role with her sweet sound and feathery delivery. Italian bass Giovanni Battista Parodi as Tom, and American bass Evan Boyer as Samuel prove to be very effective conspirators. Both are good, clear-throated singers who understand that restraint is a stronger position than melodramatic villainy. Canadian baritone Gregory Dahl shows off his robust sound in the small role of Silvano.

Conductor Stephen Lord has proven once again that he is a great dramatist, pulling out all the tension in Verdi’s music. His mastery of musical accents is superb.

I’m ending with some advice. Should this execrable Masked Ball where nothing makes sense, ever come our way again, just shut your eyes and listen to the music.

Mozart’s Così fan tutte, Canadian Opera Company, (Ensemble Studio Performance, directed by Atom Egoyan, conducted by Johannes Debus), Four Seasons Centre, Feb. 7, 2014.

Verdi’s A Masked Ball, Canadian Opera Company, (directed by Jossi Wieler and Sergio Morabito, conducted by Stephen Lord), Four Seasons Centre, Feb. 2 to 22, 2014.